|

History of the Lackawanna Valley |

|

History of the Lackawanna Valley |

NOTE: Although this is from the 1903

edition, changes in each

edition were made to the Appendix. All references to time, such as

"twenty-nine

years ago," are based on the date of the 1869 edition.

|

Pages 211 – 262

Nay-aug, or Roaring Brook, linked together by successive rapids and falls for many miles, emerges from the water-shedding crest separating the Delaware from the Susquehanna, and forms the noisiest tributary of the Lackawanna, which it enters at Scranton, one mile below the ancient village of Capoose. The woodland along the brook, unbroken on its gorgeous surface save by the achievements of the beaver, whose dams and villages deepened many a curve, had no fixed tenantry but beasts of prey until 1788.

Across the Lackawanna, the sink-clad saves had vanished from their wigwams with a sigh, leaving their fertile meadows to be tilled by men efficient in industry, yet indifferent to fear, who used the jungle now marked by Scranton, to return the visits of the wolf and the bear coming often to them unannounced. Although the great war-path from the Indian villages on the Delaware to the tribes strolling over Wyoming, intelligence of which had been early gained of the wandering bowmen, entered Capoose at the eddy affording moorage for the warrier’s canoe, no one looked upon the tamarack swamp, now hid in the interior of Scranton, as suitable for a dwelling-place, while the richer lands west of the Lackawanna, more easily cared for, invited occupancy and tillage.

Philip Abbott was the first settler in "Deep Hollow," as this place was designated from 1788 until 1798, when it took the name of Slocum Hollow. While the month of May charmed the glen with its foliage and fragrance, Mr. Abbott marked out his clearing. On a ledge of rocks, washed by the brook whose waters it overlooked, near where stands the old Slocum House, rose from the up-rolled logs the first cabin in the Hollow. It was simply a log hut or pen covered with boughs, formed but a single room, occupied in great part by a huge fire-place four or five feet in width and as many in depth, filled in the long evenings of winter with great sticks of wood before a back-log, which furnished both light and warmth to the hardy inmates. Philip was a native of Connecticut, had emigrated to Wyoming Valley with the Yankees before the Revolution, owned property under the Connecticut title, which he transferred to his brother James, both of whom were expelled by the Tories and Indians in 1778.

The settlers in Providence Township in 1788 were limited in numbers, yet their necessities sometimes pressing, found expression in the settlement of Deep Hollow. Corn and rye raised in the valley, had to be carried twenty miles to mill in Wyoming Valley, or half cracked by the pestle and mortar, and eaten almost whole. The wants of the inhabitants, multiplying gradually by the development of the settlement, and other causes wonderfully productive here in the wild woods, suggested to the practical mind of Mr. Abbott the erection of a grist-mill upon the Roaring Brook. Its waters were ample in volume and power; a dam easy of construction along its rocky grottoes. The Lackawanna, spanned by no bridge, could generally be forded during the summer months, unless swollen by rains; in winter an ice-bridge favored communication with the farmers living across the stream.

The construction of the mill was marked by strong simplicity. One millstone wrote from the granite of an adjoining ledge, slightly elevated by an iron spindle, revolved upon its nether stone as rudely and firmly adjusted upon a rock. A belt cut from skin, half wrapped on the drum of the water-wheel, passing over the spindle with a twist, formed the running gear of a mill fulfilling the expectations of its projector, and the hopes of those encouraging its erection. The mill building, upheld by saplings firmly placed in the earth, was roofed and sided by slabs hewn from trees and affixed by wooden pins and withes. Nails comprised no part of its construction, nor did the sound of the mallet and chisel take part in the triumph of its completion. No portion of the mill surpassed it bolt in novelty. A large deer-skin, well tanned and stretched upon poles, perforated sieve-like with holes, made partial separation of the flour from the coarser bran. The strong arm of the miller or customer worked the bolt. An old gentleman, now deceased, informed the writer many years ago, that when he was a mere lad "he often went to Abbott’s mill with his father, and that while the corn was being ground the old man and the miller got jolly on whisky punches in the house, while he was compelled to stay in the mill to shake the meal through the bolt." So primitive and unique was the construction of the corn-cracker, without tools or machinery, that it simply broke the kernels of corn into a samp-meal, which made a kind of food very popular in the earlier history of the valley.

The grist-mill, maintaining and even increasing its importance among the yeomanry scattered along the river, needed additional capital and labor to arrange and enlarge its capacity. These requirements came with James Abbott, in October of this year, and with Reuben Taylor in the spring of 1789, both of whom, with Philip Abbot, became equal partners in the mill. Mr. Taylor built a double log-house on the bank of the brook, below the cabin of Abbott, which was the second dwelling erected in the Hollow. Owing to the want of glass, its high, small windows, like all the cabins of the frontierman, gave place to skins from the forests. Doors, beds, and blankets, and sometimes clothes, were made from the same rich untanned material. The forest trees in the forks of the two streams, yielding to the united assaults of ax and firebrand, opened a strip of land for the reception of wheat and corn, bringing forth its maiden crop in 1789. John Howe and his unmarried brother Seth, animated by the hope that independence would come from a life of honesty and labor, purchased the rights and good-will of the former owners, and moved into the thatched dwelling vacated by Mr. Taylor. On the uplands known throughout the valley as the "Uncle Joe Griffin farm," Mr. Taylor, after rescuing a few acres from the woodlands, disposed of his place for a trifle because of its seeming worthlessness.

The first saw-mill built in Providence Township was planned on Stafford Meadow Brook, half a mile below Scranton, in 1790, by Capt. John Stafford, form whom the stream derived it name.

While the farmers living around Capoose enjoyed the prosperity and rustic comforts they themselves had created, little or no progress toward enlarging the settlement at the Hollow had been made. No building of a public character, neither school nor a meeting-house had yet been fostered within the limits of Capoose, Providence, or the Hollow. The Lackawanna led on its way, unvexed by dam or bridge. In 1796, Joseph Fellows, Sen., a man of great resolution and intelligence, who had just gained a residence on the Hyde Park hill-side, aided by the farmers of Capoose, placed a bridge across the river, with a single span. The plank used upon it was the first production of Stafford’s mill. It was located on the flats, where the slackened waters are still crossed by the throng.

That part of the certified Township of Providence now occupied by Hyde Park, originally reserved by the Susquehanna Company for religious and school purposes, was settled in 1794, by William Bishop, a Baptist clergyman of some eccentricity of character, whose log-quarters, fixed on the parsonage lot overlooking Capoose, in its rural simplicity stood where now stands Judge Merrifield’s dwelling. Most of the land about the central portion of this thrifty village was cleared by the Dolphs. In 1795, Aaron Dolph rolled up his small log-house upon the present site of the Hyde Park hotel; his brother Johathan then chopped and logged off the Washburn and Knapp farm, while the lands at Fellows Corner were brought to light and culture by Moses Dolph. The earliest house of entertainment or tavern in Hyde Park was opened and kept by Johathan Dolph. In 1810, Philip Heermans, influenced by the community, which required a public point at which to hold town meetings and enjoy the largest liberty of franchise, turned his house into a tavern, where the spirit of frolic sometimes mingled with the more sober duties of the assemblage. Elections have been held at this place ever since. On the cold soil and bleak hill north of Dunmore, Charles Dolph, another brother, moved into the forest, where he sowed and reaped in due season.

The joint and double advantage of water-power and timber everywhere found along the Roaring Brook from its mouth up to its head-springs amidst the evergreens of the Pocono, could neither be overlooked nor resisted by Ebenezer and Benjamin Slocum, who purchased of the Howes, in July, 1798, the undivided land of Slocum Hollow. The father of the Slocums was Ebenezer Slocum, Sen. He had emigrated to Wyoming Valley previous to the massacre, was shot and scalped by the Indians, near Wilkes Barre Fort, in December, 1778, with Isaac Trip, Sen.

A domestic tragedy, casting a spirit of melancholy over the brook-side cabin, hastened and impelled the transfer of the property. Lydia, the eldest born of John Howes, depressed by some disappointed visions of girlhood, was found dead in her chamber, having hanged herself with a garter attached to her bedpost. The effect of this suicide – the first in the valley – removed every speculating consideration or cavil from a trade which placed the mill and the wild acres around it into the hands of the Slocums.

Benjamin was a single man; he afterward married Miss Phebe La Fronse. Ebenezer married a daughter of Joseph Davis, one of the most eccentric medical men ever known in the Lackawanna Valley. "He was not," in the language of an octogenarian familiar with his oddities five-and-sixty years ago, "a great metaphysical doctor but a wonderful sargant doctor." Dr. Davis died in Slocum Hollow in 1830, aged 98 years.

There were now but two houses in the Hollow, and only that number of grist-mills from Nanticoke northward to the State line.

The Slocums, young, strong, and ambitious, infused new elements into the settlement. They named the place Unionville, but the name, having no descriptive interpretation or bearing to the glen, readily gave way to that of Slocum’s Hollow, or Slocum Hollow. In 1799, after the mill, necessarily rugged in its interior and external features, had been improved, enlarged, and a distillery added thereto, Ebenezer Slocum and his partner, James Duwain, built a saw-mill a little above the grist-mill. A smith shop, built from faultless logs, rose from the margin of the creek, and the sound of the anvil, carried afar, blended joyfully with the song of the noisy water. Two or three additional houses, built for the workmen, the saw and the grist mill, one cooper shop, with the smith shop and the distillery, formed the total village of Slocum Hollow or Scranton in 1800. Both dams were swept away by the spring freshet of this year, exhausting the courage of Mr. Duwain, who forthwith retired from partnership; Benjamin Slocum taking his place.

The interests of the community suffered but little, as the dams were promptly built by the aid of a bee, which called together every farmer in the township. The grist-mill was patronized far and near. Farmers twenty miles away sometimes sought the mill with their grists, and when the work was pressing on the farm at home, they tarried and toiled while the wife, heroic and devoted, went to the mill on horseback, with no equipage grander than the pillion.

The Pittston division of the valley owes no more kind remembrance to Dr. Wm. Hooker Smith for his vigorous efforts to extract iron from its hills, than the Scranton portion of it concedes to the elder Slocum brothers for the erection of the original iron-forge in the Hollow in 1800. Low down on the bank of the brook, beside the waterfall and yet above the flood, grew up the forge and trip-hammer, which, fed with the ore gathered from gullies, brought forth the molten product in abundance.

The old landmark of Slocum Hollow, cherished with pride by the old settler, is the old "Slocum House" yet standing by the creek, with its stone basement and broad long stoop, as proudly as in days of yore. It is the oldest structure in Scranton, was built in the fall of 1805 by Ebenezer Slocum, well preserved even to it capacious hearth where the fagot blazed and reflected back the light of smiling faces half a century ago, where the jest and the song went around the old hall rang to the very roof. The second frame house in the Hollow as built by Benjamin Slocum. Facing the brook, with its low porch extending along its entire front, it offered an admirable view of the forge and the sturdy artisans around it. With all these improvements along a narrow strip of clearing, Slocum Hollow was yet comparatively a wilderness. Deer, bear, and even panthers were hunted and killed here as late as 1816. Lands now occupied by the massive Round House and the Depots of the Delaware, Lackwanna [sic], and Western Railroad, were cleared of the fallen tree and sown with wheat in 1816. Six years previous, a chopping had been made where Lackawanna Avenue runs, but the wolves issuing from their fastnesses in the tamarack jungle adjoining, prevented the Slocums from keeping sheep for their much-needed wool.

Elisha Hitchcock, a young mill-wright from New Hampshire, made his way into Slocum Hollow in 1809. He repaired the mill, married Ruth the daughter of Benjamin Slocum in 1811, and excellent lady who still survives him. Mr. Hitchcock was an honest man, who never wronged his fellow, and beloved by all for his exemplary qualities; he died a few years since.

A second still was put into operation in 1811. The tranquil succession of abundant harvests throughout Capoose – the absence of an approachable market for the grain, thrashed out by the flail – the frequent calls for whisky coming from Easton, Paupack, Bethany, Montrose, and the high banks of Berwick, abating none of its value and inspirations as a commercial agent, served to welcome the accession of the new still as a public benefaction worth of the unhesitated and active patronage and favor accorded to it by every member of society.

Luzerne County, as now bounded, had but two post-offices in 1810 – Wilkes Barre and Kingston. In 1811 four were established, viz.: at Pittston, Nescopeck, Abington, and Providence. The Providence office was located in Slocum Hollow, and Benj. Slocum appointed postmaster. The inhabitants of the valley working hard for coarse food and rustic homespun, sometimes had leisure to visit and reflect, but few books or papers to peruse. Scattered through Blakeley or over the mountain, they enjoyed no mail facilities other than those offered by this office, until the establishment of another one in Blakeley in 1824. The Slocum Hollow office was removed to Providence in this year, and John Vaughn appointed postmaster. The same year William Merrifield was commissioned postmaster of a new office established at Hyde Park. The mail was carried once a week on horse-back from Easton to Bethany by Zephaniah Knapp, Esq., via Wilkes Barre and Providence; the entire mail matter for the Lackawanna settlements bore no comparison, in quantity, to the amount that very many business firms in the same vicinity are now daily the recipients of.

Frances Slocum, who was taken captive by the Indians in Wyoming Valley, in 1778, and whose subsequent history has been made familiar by Dr. Peck and Miner, was a sister of Ebenezer and Benjamin. When she was caught up in the arms of the savage that had just scalped a lad with the knife he was grinding at the door, a pointed warrior rushed into the house of Jonathan Slocum "and took up Ebenezer Slocum, a little boy. The mother stepped up to the savage, and reaching for the child, said: ‘He can do you no good; see, he is lame.’ With a grim smile giving up the boy, he took Frances, her daughter, aged about five years, gently in his arms, and seizing the younger Kinsley by the hand, hurried away to the mountains." [Miner’s History, p. 247] His release from the fickle savage, through the adroitness of his mother, was no more providential than his escape from as horrible a death in 1808. Losing his foothold while clearing the mill-race of drift-wood, he fell, and was carried by the rushing impulse of the current down the stream between the buckets of the water-wheel before he was rescued by his faithful Negro. Mr. Slocum’s weight exceeded two hundred, and yet, through this vise-like space, measuring scant six inches, he was forced with so little injury that he resumed his wonted labor within a week! Of such material, plastic yet with-like, was made the men who carved and nursed the valley in its infancy.

In the manufacture of iron, no advantage was taken of the coal ramparts by the creek, because no knowledge of its use for this purpose had reached the public mind until 1836. Charcoal, made in the turf-clad pits by the wood-side, everywhere at the furnaces asserted its prerogative as the heating agent. In fact, the timber about Scranton in the earlier part of the century was swept away, more especially to supply the charcoal demand of Slocum’s forge, than for any remunerative gain its soil promised to the cultivators of the country.

Iron forges and furnaces having sprung up in various sections of country where Slocum Hollow iron, famous for its superior texture, had been favorably know and used; the dilapidated state of the works in use for six-and-twenty years; the cost of transporting ore over miles of roads sometimes rendered impassable by fallen trees or deepened ruts; all contributed to extinguish the fore-fire. The last iron was made by the Slocums in June, 1826; the last whisky distilled a few months later. Up to this time these primitive iron-works were, in the hands of these unobtrusive men, yielding their conquests and diffusing a spirit of enterprise amidst accumulative difficulties, in a valley having no outlet by railroad, no navigable route to the sea other than shallow waters long skimmed by the Indian’s canoe.

Ebenezer retired from business in 1828; in 1832, full of years, peaceful, trusting, he went to his grave, as a shock of corn fully ripe cometh in, in it season.

Joseph and Samuel Slocum, full of youthful enthusiasm, began to carry on farming and mill interests with the same spirit of earnestness distinguishing the elder Slocums.

The obliteration of the still and forge abridged the importance and checked the growth of the village. Three roads, or rather two, cut through the woods, too narrow for wagons to pass each other only in places prepared for turn-outs, diverged from the Hollow; one from Allsworth’s, at Dunmore, led to Fellow’ Corners; while the other crossed the swamp, along what is now Wyoming Avenue, on fallen logs, and found its way by Griffin’s Corners to the acknowledged political center of the valley – Razorville village. Upper and Lower Providence, Abington, Blakeley, Greenfield, Scott, and Drinker’s Beech, offering choice wild lands to all seeking a competency by a life of frugal industry, became the home of men whose hardihood, hospitality, and staunch virtues, carried cultivation and thrift into the border of the forest, while Slocum Hollow, strangely intermingled with rock and morass, offered little to the husbandman, and nothing to the newcomer.

An effort was made in 1817 to improve the navigation of the Lackawanna, and a company incorporated at the time for this purpose; nothing more was done. In 1819, the late Henry W. Drinker – than whom no man surpassed in readiness to aid the needy pioneer or develop the resources of the country – explored the mountains and valleys from the Susquehanna at Pittston to the Delaware Water Gap, with a view of connecting the two points by a railroad to be operated over the Lehigh Mountain by hydraulic power achieved from the waters of Tobyhanna and the Lehigh.

While the Slocum Hollow settlement, being on the line of the proposed road, was expected to acquire some increased activity mutually advantageous, the interests of Drinker’s Beech, watched carefully by Mr. Drinker, were more especially aimed at by the projectors of the road. A charter was granted in March, 1826; simultaneously a charter was obtained by Wm. Meredith, for a railroad to run up the Lackawanna to the State line from Providence village. Both were projected upon the plan of inclined planes.

The four pioneers obtaining railroad charters in the Lackawanna Valley were Wm. And Maurice Wurts, Henry W. Drinker, and Wm. Meredith. The first two gentlemen banded the mountains’ brow with the flat rail; the last, owing to needless antipathies which aroused every impulse of selfishness, and embittered even the calm hour of triumph with its remembrance, were not able to infuse into charter easily obtained, advantage to themselves or to the places they sought to enrich and develop. These men were powerful in the day of the first railroads; polished opulent, and educated, and had there been united and harmonious action among them, the valley would hardly have been so reluctant in yielding the wherewithal to gladden the firesides of the land. Drinker, averse to a strife fatal to his cherished projects, shared none of the prejudices against the men who had rendered practicable an eastern outlet from the valley.

The north Branch Canal, fed by the idle waters of the Lackawanna, was begun in Pittston in 1828 by the State, and looked to as the great commercial avenue to the sea. The citizens of old Providence Township, restrained by the mountain’s wall from all hoe of public intercourse with Philadelphia or New York by a continuous railroad, withal too modest to expect a canal a the expense of the State, asked the Legislature, having but a negative representation from the valley, to build "the feeder of this canal, or some other improvement up the valley as far as would be thought of service to our citizens and the Commonwealth."

This scheme naturally excited the public mind, because its prosecution under any circumstances would reach out benefits to every husbandman jealous of his own rights, yet taught by invidious men to distrust the power of "incorporated companies." [See "Wilkes Barre Advocate," December 9, 1833]

The coal clad slopes enjoyed repose. The cesarean drill had not yet fallen into the strong arms of the skillful miner. Up in Carbondale glen, under the shelter of a ledge of rocks forming the western bank of the Lackawanna, a few hundred tons of surface coal had been mined by the Wurts brothers as an experimental measure. The operations of these weather-beaten, persecuted, yet hopeful men, were not recognized by the inhabitants of the lower townships as of any practical utility to any one but the miners themselves. Wood was abundant, and every hill-side offered fuel to the woodman who chose to gather it without cost. Coal had neither domestic value nor sale at home; no market abroad. A brighter aspect at length struggled it way into the valley, and the solitude of Slocum Hollow as gone.

"About 1836," says Mr. Joseph J. Albright, in a note to the writer, "at the suggestion of Geo. M. Hallenback I made the trip to Slocum Hollow for the purpose of examining the iron ore, coal, &c., with a view of purchasing from Alva Heermans the property (now Scranton) for $10 per acre. I took a box of the iron ore on top of a stage to Northampton County, where I was engaged in the manufacture of iron, and I contend that I shook the first tree, if I failed to gather its fruit. I believe the box of ore thus transported was the means of attracting the attention of Messrs. Henry, Scranton, &c., to this tract. These facts are known and recognized by S. T. Scranton; had I been successful in persuading Dr. Philip Walter and others to join me in its purchase, I might have gather ample reward."

Drinker’s route for a railroad from the Delaware to the Susquehanna, surveyed in 1831 by Maj. Beach, awakened neither interest nor inquiry among the yeomanry having scarcely means to meet the yearly taxes or support families generally large and needy, and yet, strange as it may appear, the initial impulse toward a village at Slocum Hollow came from the friends of this project. William Henry, one of the original commissioners named in the charter, was especially enthusiastic and active in his efforts to build up a town at this point for the purpose of advancing the interests of this unattractive project. His knowledge of the country was too thorough and general to be without its stimulating influence, and yet this acquaintance of the mineralogical character of the western terminus of the route only enabled him to give decided expression to view neither adopted nor accepted by his friends.

Messrs. Drinker and Henry, undismayed by the cold, solemn avowal of the inhabitants occupying the valleys of the Delaware and Susquehanna, that no such road was possible or necessary to their social condition, taking advantage of the speculative wave of 1836, called the friends of the road to Easton at this time to devise a practical plan of action. Repeated exertions in this direction had hitherto yielded a measure of ridicule not calculated to inspire great hopes of success. At this meeting, prolonged for days, Mr. Henry assured the members of the board that if the old furnace of Slocum’s at the Hollow could be reanimated and sustained a few years, a village would spring up between the unguarded passes of the Moosic, calling for means of communication with the seaboard less inhospitable and tardy than the loitering stagecoach. This novel plan to achieve success for the road, although urged with ability and candor, met the approval of but a single man. This was Edward Armstrong, a gentleman of great benevolence and courtesy, living on the Hudson. In the acquisition of land in the Lackawanna Valley, or the erection of furnaces and forges upon it, he avowed himself ready to share with Mr. Henry any responsibility, profit, or risk. During the spring and summer of 1839, Mr. Henry examined every rod of ground along the river from Pittston to Cobb’s Gap to ascertain the most judicious location for the works.

Under the wall of rock, cut in twain by the dash of the Nay-aug, a quarter of a mile above its mouth, favoring by it altitude, the erection and feeding of a stack, a place was well chosen. It was but a few rods above the debris of Slocum’s forge, and like that earlier affair enjoyed within a stone’s throw every essential material for its construction and working.

After the decease of Mr. Slocum, the forge grounds changing hands repeatedly for a mere nominal consideration, had fallen into possession of William Merrifield, Zeno Albro, and William Ricketson of Hyde Park, and had relapsed into common pasturage. Mr. J. J. Albright was offered 500 acres of the Scranton lands for $5,000 upon a long credit in 1836; for such land that figure was considered too high at that time.

In March, 1840, Messrs. Henry and Armstrong purchased 503 acres for $8,000, or about $16 per acre. The fairest farm in the valley, under-veined with coal, had no opportunity of refusing the same surprising equivalent. Mr. Henry gave a draft at thirty days on Mr. Armstrong, in whom the title was vest; before its maturity, death came to Mr. Armstrong, almost unawares. He had imbued the enterprise, by his manly co-operation, with no vague friendship or faith, and his death, at this time, was regarded as especially disastrous to the interest of Slocum Hollow. His administrators, looking to nothing but a quick settlement of the estate, requested him to forfeit the contract without question or hesitancy. Thus baffled in a quarter little anticipated, Mr. Henry asked and obtained thirty days’ grace upon the non-accepted draft, hoping in the interim to find another shrewd capitalist able to advance the purchase-money and willing to share in the affairs of the contemplated furnace. The late lamented Colonel Geo. W. Scranton and Selden T. Scranton, both of New Jersey, interested by the earnest and enthusiastic representations of Mr. Henry regarding the vast and varied resources of the Lackawanna Valley, of which no knowledge had reached them before, proposed to add Mr. Sanford Grant, of Belvidere, to a party, and visit Slocum Hollow.

The journey from Belvidere to the present site of Scranton took one day and a half hard driving, and was well calculated to test the self-reliance and vigor of the inexperienced mountaineer. The Drinker Turnpike, stretching its weary length over Pocono Mountain and morass, enlivened here and there by the arrowy trout-brook or the start of the fawn, brought the party on the 19th of August, 1840, to the half-opened thicket growing over the tract where now Mr. Archbald’s residence is seen. Securing their horses under the shad of a tree, the party, amazed at the simple wilderness of a country where green acres were looked for in vain, moved down the bank of Roaring Brook to a body of coal whose black edge showed the fury of the stream when sudden rains or thaws raised its waters along the narrow channel. None of the party except Mr. Henry had ever seen a coal-bed before. Assisted by a pick, used and concealed by him weeks before, pieces of coal and iron ore were exhumed for the inspection of the party about to turn the minerals, sparkling amid the shrubs and wild flowers, to some more practical account. The obvious advantages of location, uniting water-power with prospective wealth, were examined for half a day without seeing or being seen by a single person.

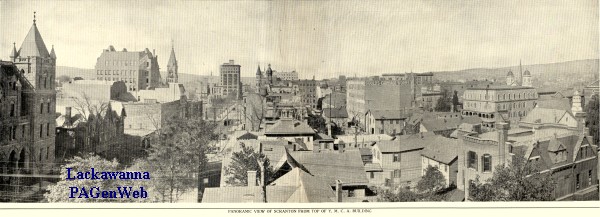

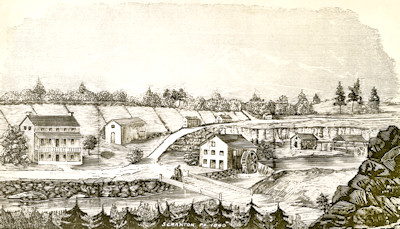

Slocum Hollow (Now Scranton) in 1840

(click on the picture for a full size image)

The village of Slocum Hollow, in 1840, yielded the palm to the surrounding ones. The Slocum house [at the left in the sketch above] and its humble barn, three small wooden houses, and one stone dwelling, outliving the days of the forge, stood above its debris; a grist-mill, owned by Barton Mott, a seven-by-nine school-house squatting on the ledge, and a clattering saw-mill, made up the village twenty-nine years ago.

The exterior features of the Slocum property were any thing but attractive, yet, after some question and hesitancy, it was purchased at the price already stipulated. Lackawanna Valley achieved its thrift and fame from this comparatively trifling purchase of but yesterday, and Scranton dates its incipient inspirations toward acquiring for itself a place and a name from August, 1840.

The company, consisting of Colonel George W. and Selden T. Scranton, Sanford Grant, William Henry, and Philip H. Mattes, organizing under the firm of Scrantons, Grant & Co., began forthwith the construction of a furnace, under the superintendency of Mr. Henry, whose family immediately removed from Stroudsburg to Hyde Park.

None of the older portion of the community can forget the thriftless appearance of the four villages in Providence Township, exhibiting no reluctant spirit of rivalry. Hyde Park contained but a single store, where the post-office found ample quarters in a single pigeon hole; a small Christian meeting-house standing by the road-side, and six or eight scattered dwellings along the single roadway; neither physician, lawyer, nor miner, and but a single minister, without a church of his own, resided within its precincts. Providence, known far and wide by the sobriquet of Razorville, acknowledged as the seat of government for the county, had a dozen houses, two stores and a post-office, a grist-mill and a bridge, an ax factory, three doctors, no minister, and it did a snug business in the way of horse-racing on Sunday, and miscellaneous traffic with the round-about country during the week. Dunmore was the equal of Slocum Hollow in the number of its dilapidated tenements, sheltering as many families. Such were the towns that gave a negative welcome to the innovations of the unknown "Jerseyites," as they were termed, in half derision, by people hearing of their search and purchase around Capoose.

New men naturally introduced new names. When the white man first strayed into the valley, no other name than Capoose – an Indian signification of endearment – was heard until the connection of the Slocums with the rough hollow, in 1798, opening land and trade, fixed the appellation of Slocum Hollow. The memorable days of "hard cider" substituted the name of Harrison for that of Slocum Hollow. The Scranton, not without ambition to popularize a name never dishonored, assented to the exchange of Harrison for Scrantonia. With the growth and triumphs of the iron-works, the brief vowels ia were erased, leaving plain Scranton in possession of the field. This name thus serves to perpetuate the memories of the founders of the town, but would not the aboriginal Capoose or the Indian names for the streams, Nay-aug or Lar-har-har-nar, have been more musical and appropriate?

The first day’s work on the Harrison furnace was done September 11, 1840, by Mr. Simeon Ward. During the fall and winter months satisfactory progress attended it. A small wooden building, afterward enlarged for "Kresler’s Hotel," was erected by W. W. Manness, who is yet in the employ of the company, and jointly occupied as an office, store, and dwelling. It was afterward torn down to make room for the blast-furnace engine-house. As the spring of 1841 opened, tenant-houses went up, and work went forward without cessation or abatement. Mr. Grant became a resident of Harrison, with his family, and for many years, when the tide was low, conducted the management of the store with such urbanity and studied regard for the interests of all, that he acquired consideration and popularity among the yeomanry of the county.

The interests of P. H. Mattes were represented by his son, Charles F. Mattes, who, from the time the furnace was put in successful blast, has been efficiently engaged at the head of one of the more important departments.

The liberal doctrines of Methodism, itinerated and diffused in the valley as early as 1786, were rarely practiced, and had but a feeble recognition in any way until 1793. "At this time," writes the venerable Rev. Dr. Peck, "William Colbert, a pioneer preacher, visited Capouse [sic], and preached to a few people at Brother Howe’s, and lodged at Joseph Waller’s. Howe lived in Slocum Hollow, and Waller on the main road in or near what is now Hyde Park. In 1798 Daniel Taylor’s, below Hyde Park, was a preaching place. For years subsequently the preaching was at Preserved Taylor’s, who lived on the hill-side in Hyde Park, near the old Tripp place. When Mr. Taylor removed, the preaching was taken to Razorville, now Providence, and the preachers were entertained by Elisha Potter, Esq., whose wife was a very exemplary member of the church. Up to this period, preaching was held in private houses." School-houses, moderate in capacity, served for religious purposes until June, 1841, when a subscription was raised for the purpose of building a "meeting-house" at some suitable place within reach of missionaries and laymen. The great bulk of the subscription coming from Harrison Iron Works, governed the location of the church, which was built in 1842, and jointly and harmoniously used as a place of worship by Methodists and Presbyterians until the latter erected a place of their own. The Methodists have enjoyed the pastoral labors of A. H. Schoonmaker, Rev. Dr. Peck, B. W. Goram, G. C. Bancoft, J. V. Newell, J. A. Wood, N. W. Everett, and Byron D. Sturdevant.

The Presbyterians now representing so much of the intelligence and wealth of the Scranton community, had no definite organization in Scranton until February, 1842. In 1827 missionaries were employed to preach at Slocum Hollow and Razorville twelve times a year, generally in school-houses and barns, and sometimes under the shelter of a friendly tree. Rev. Cyrus Gildersleeve, John Dorrance, and the bold, blunt Thomas P. Hunt, were thus employed alternately. The success attending the Methodists in building their church by subscription, animated the fewer Presbyterians to a similar effort in the same direction. The pressure of poverty among the farmers of the valley, combined with the weak condition of this denomination, having but four members at Harrison, influenced the committee appointed in 1844 to select a site for a church, to decide upon Lackawanna, three miles below Harrison, as the place best calculated to favor the majority of the Presbyterians. The church, built in 1846, was owned in common by the members at Lackawanna and Harrison. This latter place was a mere subordinate preaching point, and yet cared for so well by the young, gifted Rev. N. G. Parks, that in 1846 the Scranton portion of this organic body, acquiring influence and independence with the development of the village, sought a peaceful separation, and at once asserted its strength by the erection of an imposing church, costing $30,000, capable of seating 800 person. Since Mr. Park, the Rev. J. D. Mitchell, John F. Baker, and the Rev. M. J. Hickok, have all creditably officiated within its walls. Mr. Hickok, whose purity of mind and blameless life endeared him to all, was hopelessly stricken with paralysis in the fall of 18676, thus leaving the church without an active pastor.

The spiritual wants of the Catholics in Scranton were first looked after by the Rev. P. Pendergrast in 1846. A small room in a private dwelling served for a gathering place until 1848, when a church, 25 by 25, was constructed. The constant accession of numbers rendered a larger place of worship necessary in 1853-4, under the attention of the Rev. Father Moses Whittey. The erection of a Catholic church in Providence and another in Dunmore, drew somewhat from a congregation yet so numerically strong in Scranton, that Father Whittey, well known for his calm deportment yet zealous devotion to the interests of his church, looking to the future want and welfare of his flock, began in 1864 to build a cathedral, at an estimated cost of $100,000. The edifice is built in the Grecian style of architecture, 68 by 158 feet, and will seat 2,300 persons. Few individuals in the valley could have turned so powerful an influence to the greater advantage of Scranton than has Father Whittey done in the erection of this edifice.

The first Baptist church here was built under hopeful auspices in 1859; in 1863, the Rev. Isaac Bevan, acting in concert with those fostering the project, increased his claim to public gratitude by the erection of a brick sanctuary, 50 by 80, at a cost of $40,000. The church numbers about 200 communicants.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church dates back only to 1852. Within the next eighteen months, a frame church and parsonage were finished and completed at a cost of about $4,000. St. Luke’s is now so comparatively wealthy and popular in Scranton, that a new stone church is being erected for a Parish, at a cost of $150,000. This ecclesiastical body, eschewing politics and religious ultraism, has, under the ministerial administration of Rev. John Long, W. C. Robinson, and the Rev. A. A. Marple, the indefatigable, gentlemanly pastor, grown into public favor in an especial manner since its original existence here.

The German Presbyterian Church of Scranton was dedicated in 1859; the Evangelical Lutheran Zion Church, organized in 1860, purchased the First Welsh Baptist Church in Scranton in 1863.

The Liberal Christian Society have a respectable organization without enjoying a place of worship of their own.

The German Catholics, looked after by their worthy pastor, Rev. P. Nagel, built them a neat edifice in 1866, at a cost of $11,000.

The above-named churches, enumerating only those embraced within the old village proper of Scranton, are named in the order of their development.

The fact is indeed creditable to the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company, that a great portion of the land occupied by these respective places of worship, was generously donated by them for this specific object.

History of Scranton Excerpts from Craft, Wilcox, and Wooldridge

History of Providence and Dunmore from Hollister

Transcription of Hollister's Second Edition of 1869

Return to Index of History

Return to the Lackawanna County PAGenWeb Home Page